Sometimes they are one and the same.

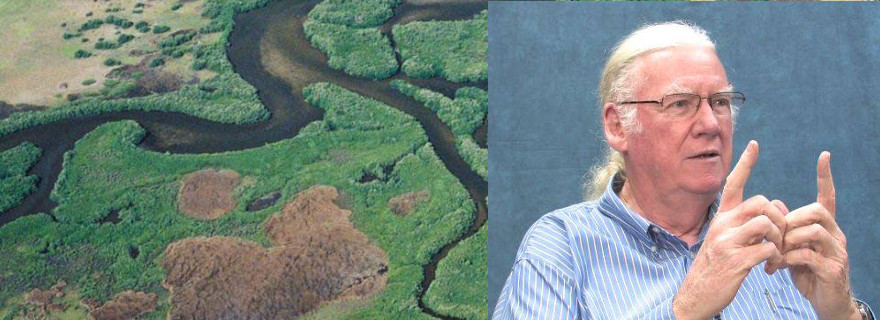

That is the case with Robin Lewis. A big man with big ideas and a bigger heart, Robin died recently at age 74 at his home in Marion County. His passing resurrected memories of this true champion of Tampa Bay, and a somber reflection on the loss of his contemporaries – Jan Platt, Roger Stewart, Rich Paul, John Betz and others who stirred up “good trouble” to make the recovery of Tampa Bay the international success story it is today.

“In my opinion, it’s in better shape than any estuary on the planet,” Robin said in a 2016 interview for an Oral History project sponsored by the University of South Florida. “And I believe I contributed to that along with hundreds of other people who took a very early interest in the biology of the bay.”

Robin never was one to parse words.

Robin left Tampa Bay for a home in Ocala National Forest a decade ago. By then, he was an internationally recognized wetlands scientist, who designed and consulted on mangrove and seagrass restorations around the world, authored numerous scientific papers and was featured in dozens of mainstream publications, including Scientific American and the Smithsonian’s Oceans website. But he cut his teeth here, first as a young biology instructor at Hillsborough Community College and later as an outspoken environmental consultant with a natural talent for distilling science-speak and a showman’s flair for connecting with an audience.

In 1985, Robin completed one of the bay’s first saltwater habitat restorations, a mangrove wetland at a high-rise office and hotel complex on Rocky Point. Visit the Grand Hyatt today, walk along the boardwalk connected to the hotel and tell the roseate spoonbills who dine there daily that Robin sent you.

“This isn’t rocket science,” he would say of the nuts-and-bolts work of piecing a broken Tampa Bay together again. “Get the hydrology right and the rest is easy.”

Robin was an early member of Save Our Bay, a 1970s coalition of citizens and scientists from HCC, the University of South Florida and the University of Tampa. Together they sounded the alarm about the bay’s steep decline – the result of years of discharges of barely treated sewage and unregulated dredging and filling.

“Hillsborough Bay was so polluted I remember diving in the bay and not being able to see my hand in front of my face,” he once told me.

Not everyone had air conditioning in the 1970s, and the situation allegedly became so dire that the rotten-egg fumes from decaying mats of algae exposed at low tide wafted into the open windows of the moneyed elite of Tampa’s Bayshore Boulevard, causing the family silver to tarnish. When they got riled up, Robin said, the powers-that-be took notice.

Aided by the new Earth Day consciousness sweeping the nation, laws requiring better sewage treatment were passed and dredging restricted. In 1979, completion of Tampa’s new state-of-the art wastewater treatment plant marked a turning point for Tampa Bay. The waters gradually grew clearer, fish and birds returned, and seagrasses began to sprout and spread again on the bay bottom. Record seagrass acreage was observed in 2016, exceeding the ambitious goal set by bay managers 20 years earlier. Robin went on to design and implement numerous restorations in Tampa Bay, to help found the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and Tampa BayWatch, and to advocate relentlessly for the bay’s well-being.

He was hired by large corporations like TECO and Mosaic to implement restoration and mitigation projects but didn’t hesitate to criticize them either. He became successful, selling his first firm, starting another, investing in a mitigation bank, even opening an office in the Florida Keys. Former employees remember that Robin gave away more money than he saved, supporting causes and projects he believed in, and at times monitored projects for far longer than he was paid to, because he wanted to learn which techniques worked and which didn’t.

He was hired by large corporations like TECO and Mosaic to implement restoration and mitigation projects but didn’t hesitate to criticize them either. He became successful, selling his first firm, starting another, investing in a mitigation bank, even opening an office in the Florida Keys. Former employees remember that Robin gave away more money than he saved, supporting causes and projects he believed in, and at times monitored projects for far longer than he was paid to, because he wanted to learn which techniques worked and which didn’t.

When it came to his work, his first concern was always for the resource, said Dan Savercool, a senior scientist at EA Engineering, Science, and Technology, Inc., who was an early employee of Robin’s and later his business partner in Lewis Environmental Services.

“He always came down on the side of science. He understood the importance of data, and what the data showed. That approach pointed the path for him throughout his professional and personal life,” Savercool said.

Former Tampa Tribune editorial writer Joe Guidry remembers relying on Robin and Jan Platt for straight talk when the Tribune launched a comprehensive Saving the Bay editorial series in the 1980s.

His boss at the time, Editorial Page Editor Ed Roberts, was supportive but, as a conservative, his instincts did not naturally hew to the side of environmental protection. Guidry used to arrange for Robin to come to the Tribune to give Roberts background briefings on bay issues. Robin employed his own brand of “kitchen diplomacy” on these occasions.

“Robin used to bring his delicious home-made clam chowder in a crock pot,” Guidry recalled. “We would have it for lunch at the Editorial Conference table, as Robin talked about the importance of restoring the damaged sections of the bay, reviving seagrass, cleaning up stormwater and such. Ed became an enthusiastic supporter of my Tampa Bay editorials.“

In the 1980s TECO proposed building a power plant near Cockroach Bay, one of the bay’s most productive and pristine areas. Guidry recalls a boat trip he arranged with Robin to show Roberts the waters surrounding the proposed power plant.

“Robin got out of the boat and dipped down a clear plastic bucket into the water. When he pulled it up, it was teeming with life, including juvenile shrimp and tiny fish. ‘This,’ he told Ed, ‘is what’s at stake.’” The power plant was never built.

My own recollections of Robin begin in 1987, when I joined the Tampa Tribune as a reporter covering environmental issues. Robin was a trusted and reliable source of science-based information about the bay, and he knew how to dole out a great quote. He allowed me to tag along on monitoring trips, back in the days when having a newspaper “beat” meant building relationships, talking to people face-to-face, and seeing areas I wrote about firsthand. Much of what I learned about Tampa Bay came from Robin and Audubon warden Rich Paul, and I will forever be grateful for their patient tutelage.

I am a proud graduate of the “Lewis School of Local Ecology,” which usually meant trailing after Robin, an imposing figure well over 6 feet tall, while sinking ankle-deep in the soft mud of the bay’s mangrove forests. We sometimes fueled up for those endurance trials with lively breakfasts at the old Giant’s Fish Camp restaurant on US 41 at the Alafia River.

Mine was not the only career that Robin had a hand in shaping. He hired smart, energetic and passionate young environmental scientists at his first consulting firm, Mangrove Systems, and its successor, Lewis Environmental Services. One of those was Sally Treat, who worked for him 15 years.

“I started as a summer field hand, laying sod and planting cattails at a power plant in Lakeland,” Treat said. She then moved up to secretary, office manager and technical editor in charge of proposal and report preparation, grabbing field time whenever an opportunity came along to plant seagrasses or conduct wetland delineations.

Treat said Robin was a “huge part of not just my life but so many of my fellow grad students at USF. He kept us employed through some tough times, and turned us into a bunch of really good people.

“The whole time I worked for and with Robin, I felt like he was providing me with the greatest opportunities I could ever have. He knew how to make things grow.”

Savercool sent Robin an email in June telling him of the profound impact Robin made on him as an environmental professional. He said Robin’s role as a mentor was among his most important, and one that he was uncharacteristically quiet about.

“He wanted to share his knowledge with everyone,” Savercool said. “It didn’t matter whether you agreed with him or not. He was always willing to take the time to share what he had learned.”

By Nanette O’Hara, originally published October 23, 2018.

Learn More

Tampa Bay Estuary Oral History Project

http://exhibits.lib.usf.edu/exhibits/show/ohp-tampabayestuary

“Giant” Restoration is Prototype for Tampa Bay Mangroves (Bay Soundings)

http://baysoundings.com/giant-restoration-is-prototype-for-tampa-bay-mangroves/

Lack of Tidal Flow Killing Mangroves Around the World (Bay Soundings)

http://baysoundings.com/lack-of-tidal-flow-killing-mangroves-around-the-world/

Hard Times for Tampa Bay Oysters

http://baysoundings.com/legacy-archives/wint04/bayoysters.html

To explore a little more about Robin’s work- https://pin.it/5b2huhitcmhqzp

[su_divider]