Terry Fluke doesn’t hesitate when asked about the importance of PORTS®, Tampa Bay’s Physical Oceanographic Real-Time System. “It’s mission-critical for our members,” says the executive director of the Tampa Bay Harbor Pilots Association, the group charged with piloting ships in and out of Tampa Bay.

- PORTS® transmits real-time data on weather conditions to harbor pilots who can then make better-informed decisions

- PORTS® is the first system of its kind in the U.S. Since it was implemented in Tampa Bay, accidents have dropped by two-thirds.

- Originally funded through the phosphate severance tax, those moneys are drying up as mining moves south. Bay managers are searching for a permanent source of funding.

PORTS® is an integrated system of oceanographic and meteorological sensors that provide mariners with reliable real-time information about environmental conditions in seaports. In concert with nautical charts and other navigational aids, this “coastal intelligence” helps mariners make better decisions about safety and cargo.

With PORTS®, harbor pilots and mariners can access real-time measurement of winds, waves, currents, tides, visibility, bridge clearance and other data at critical locations – information that is vital to safe navigation.

No Margin for Error

More than 3,000 ships call on Tampa Bay each year, from cruise and container vessels to tankers and barges, some the length of modern skyscrapers. “As far as a margin of error, there is none,” says Fluke. “We have to be 100% correct 100% of the time – that’s our goal, and everything PORTS® offers dovetails perfectly into that mission.”

More than 4 billion gallons of oil, fertilizer components and other hazardous materials pass through Tampa Bay each year, including roughly 45% of Florida’s petroleum.

Tampa Bay is home to three seaports: Port Tampa Bay, Port Manatee, and the Port of St. Petersburg, where one of the Gulf of Mexico’s largest U.S. Coast Guard commands is based. Port Tampa Bay is the largest, most diversified port in Florida, encompassing more than 5,000 acres near downtown Tampa, and handling more than 37 million tons of cargo and a million cruise ship passengers per year.

Port Manatee, the closest U.S. deepwater port to the Panama Canal, manages approximately 10 million tons of cargo per year, ranging from tropical fruits and vegetables, citrus juices and beverages to fertilizer and petroleum products.

Unlike many other deepwater ports around the country, Tampa Bay’s main shipping channel is long, narrow and winding, stretching 44 miles from the buoy at Egmont Key to a berth at the Port of Tampa; average trips take four hours. Heavy winds, tropical storms, and miscalculations – even minor ones — can result in groundings.

Tragedy on the Bay

One major maritime accident can cost tens of millions of dollars in property loss, environmental damages and harbor closings; a catastrophic event can cost human lives.

Such was the fate of the Summit Venture on the morning of May 9, 1980, as it headed from the Gulf of Mexico to the Port of Tampa. Battling tropical storm force winds and heavy rain, with nearly zero visibility, the ship lost its radar, rendering it essentially blind on its approach to the Sunshine Skyway Bridge. High winds and currents pushed the 20,000-ton freighter out of the channel and into the main support pier of the bridge, causing a portion of the suspended roadway to collapse. Six cars, a truck and a Greyhound bus fell 150 feet into the water, killing 35 people.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, Coast Guard and NOAA officials suggested that the use of real-time oceanographic data and meteorological sensors may have helped to avoid the collision. In response to the Skyway incident, Tampa Bay established the first PORTS® system in the nation in 1991. Today, PORTS® systems operate coast to coast in 35 major seaports, about one-third of all U.S. seaports.

PORTS® Saves Lives

Since PORTS® became operational in Tampa Bay, ship groundings here have decreased by two-thirds. Nationally, accidents have decreased by 59% in seaports currently served by PORTS®. Injuries are down 45%, and property damage has fallen 37%. Most notably, the number of deaths associated with marine accidents has declined by 60%.

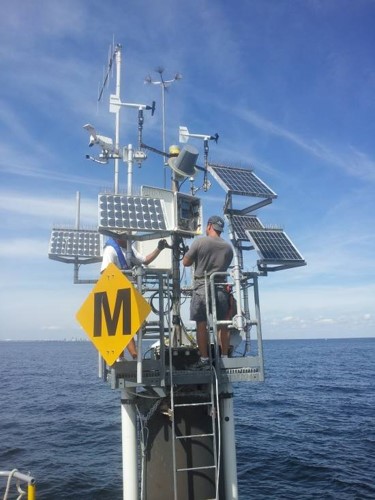

Since 1991, Tampa Bay PORTS® has expanded from 12 sensors at eight sites to 34 individual sensors at 14 locations, including an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler installed at the sharp turn into Port Manatee Channel as well as additional wind measurement sites to support cruise ship transits, and visibility sensors critical to navigating in heavy fog.

NOAA manages PORTS® through agreements with local partners, who typically contract with the agency for equipment and maintenance. Locally, PORTS® is operated through the non-profit Greater Tampa Bay Marine Advisory Council, with in-kind support from the USF. See Funding PORTS®.

“We’re constantly upgrading and expanding the system, says Mark Luther, director of the Ocean Monitoring and Prediction Lab at USF’s College of Marine Science, who has overseen operational and maintenance support for PORTS® since 1995.

“It’s a big challenge keeping sensitive electronics working around saltwater,” he says. Sensors break, batteries eventually die, storms damage and destroy equipment. “When we’re not fixing things, we’re looking for funding to upgrade aging infrastructure.”

Most sensors, Luther notes, date back to 1991. Upgrading to newer technologies that have become available since then would make data transmission even more reliable, easier to maintain, and better able to withstand the harsh elements.

At several sites, data is still transmitted by VHF radio, which works only if receiving and sending antennas are within “line of sight” – a range of about 30 miles, Luther explains. Replacing them with satellite and cellular transmissions at six sites would require a $90,000 one-time investment.

“I can remember laying out our first water meter in Old Port Tampa to capture critical current movements because we had tankers moving oil in and out,” recalls George Viso, president of the American Pilots Association and a former Tampa Bay harbor pilot. “Back then, before cell phones, we had to have radio dispatchers call us with current readings.

“PORTS® is indispensable — it gives us precision information about changing conditions and lets you know what your safe operating windows are.”

Bay managers renew call for permanent funding for PORTS®

It’s been a question of longstanding concern in the bay management community. What happens when PORTS® largest funding source dries up?

PORTS, the nation’s first integrated network of oceanographic and meteorological sensors, was established in Tampa Bay in 1991. Revenues from Hillsborough County’s Phosphate Severance Tax are PORTS largest single source of funding, providing $150,000 for annual maintenance and operations. But tax revenues have declined sharply in recent years as once-vast deposits of the fertilizer mined in Hillsborough County are depleted.

Phosphate severance tax revenues – which also help fund mining reclamation and wetland restoration projects – averaged just over $1 million annually from 2013 to 2016. As mining activity in the county winds down, revenues have shrunk by more than 57 percent with just $575,000 projected for 2020.

Thanks to gap funding from Hillsborough County general revenues, allocations for PORTS and other severance tax revenue-dependent programs have remained steady — for now. “We’re watching the fund pretty closely, and at this juncture, we will continue to supplement it as needed” says Kevin Brickey, director of Hillsborough County’s Office of Management and Budget. “But as far as what happens when it ends, we haven’t gotten that far.”

Meanwhile, anticipating the eventual end of phosphate tax revenues, other funding partners have stepped up their contributions. Port Tampa Bay’s commitment jumped from $15,000 per year to $100,000 in 2019, funded through an increase in port harbor fees on commercial cargo vessels and cruise ships. The Tampa Bay Harbor Pilots also increased their support to $12,000, and Port Manatee became a first-time funder, pledging $10,000 for 2020.

Funding increases for 2020 will enable PORTS to begin replacing and upgrading its aging infrastructure. “We have a lot of equipment on its last leg,” says Luther. “Most of our current sensors are about 20 years old; it’s questionable how much longer they’ll be serviceable.”

Making Funding Permanent

PORTS long-term viability hinges on securing permanent funding, say leaders in the bay management community. In fact, that goal was originally set in the Tampa Bay Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP) adopted in 1997. But that hasn’t been accomplished.

Without securing permanent funding commitments, PORTS is vulnerable year-to-year budget cuts, potentially compromising its future. For a system deemed mission-critical to navigational safety, that’s unacceptable.

“It’s been hard to build support when a lot of the people involved in bay management don’t view it as their responsibility,” said Maya Burke, science policy coordinator for the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and a former member of the Tampa Bay Harbor Security Committee. “We have multiple funding sources and other potential ones identified, but what we’re really looking for is permanent funding from all parties. And we should be reporting (progress) on this annually to the Agency on Bay Management (ABM), but that hasn’t happened.”

Burke pressed the issue in 2015 at a joint meeting of ABM and TBEP while it was updating the CCMP. It was initially proposed that the call for establishing permanent PORTS funding be retired from the update. “We needed to correct the assumption that it’s fine, we’ve done it,” she said.

While ultimately successful in keeping the action in the plan, actually getting the job done will require accountability and follow through, Burke says.

“It’s scary to think that this need remains,” adds Ed Sherwood, executive director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program. “You don’t have to look back too far to when a major oil spill resulted from a ship collision in Tampa Bay. It’s paramount that mariners have PORTS® available for navigation.”

“I’ve been hearing for the past 10 years that phosphate mining in the county is going to be done in five years,” said Tom Ash of the Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County. “It’s not a matter of if but when. We’ve got to make funding permanent – and soon.”

Reported and written by Mary Kelley Hoppe