Stormwater retention ponds have been the easy alternative for developers ever since stormwater treatment rules were enacted in the mid-1980s. As parts of the region are redeveloped, though, ponds that require large amounts of space are no longer first choice for reducing nutrient loads in stormwater.

Legislation passed in 2012 encourages FDOT to look at out-of-the-box approaches that offer similar or greater water quality improvements. Recognizing that Old Tampa Bay is still considered to be the bay’s “problem child,” the Florida Department of Transportation is proposing to build a 200-foot bridge, replacing part of the Courtney Campbell Causeway just west of the Ben T. Davis Beach to restore tidal flows and improve water quality.

“Even though roadways don’t generate nitrogen loads, they collect them,” notes Dave Tomasko, principal associate at ESA, one of FDOT’s environmental consultants. “Wet stormwater ponds only remove 30% to 40% of the nitrogen loads coming into them. The only thing close (to 100% removal) is dry retention but FDOT would have to build an elevated dry retention pond with a bottom so high that we’d need to pump the water up to separate the pond from the water table.”

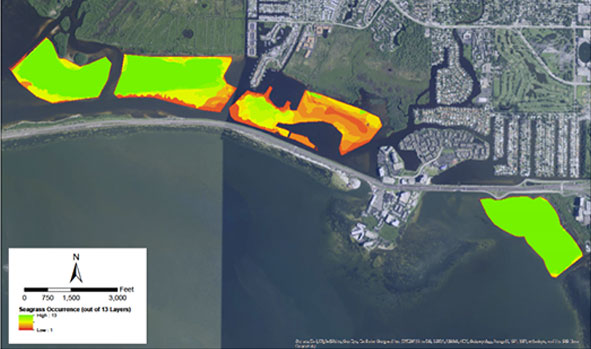

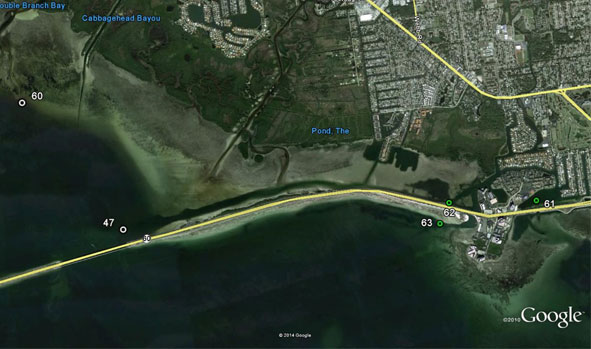

FDOT’s consultants were able to show that the reduced coverage of seagrass north of the Courtney Campbell is mostly due to variations in the saltiness of the water and not from pollutants carried in runoff. “The issue here isn’t as much nitrogen as it is salinty,” Tomasko said. Most of the seagrasses growing in the section furthest away from the bridge is wigeon grass (Ruppia maritima), a pioneer species highly tolerant of lower salinity that probably wasn’t the dominant species there in the past. it} More productive seagrasses are denser in the areas closer to the bridge where tidal flow is more consistent.

A series of studies indicates that the opening will improve water quality and potentially restore enough tidal flow to support another 80 acres of desirable seagrass species, as seagrasses from nearby areas expand, Tomasko adds.

The Southwest Florida Water Management District, which will make the final decision on whether a permit should be granted, supports the concept in theory. “The legislature is pushing for flexibility so we’re taking the idea to the community for vetting,” notes Dave Kramer, the district’s surface water regulation manager. “It will be the first mitigation of its kind in the state.”

While some stormwater retention ponds are still planned to allieviate flooding and collect oil and trash from the roadway, addressing nutrient pollution in highly developed areas would require “literally buying office buildings to build ponds,” Kramer adds.

Constructing this restoration project in the receiving waterbody will allow FDOT to reduce pond sizes associated with future projects and realize a cost savings on right-of-way purchases, say FDOT officials.

Historic problem

Old Tampa Bay has lagged behind other bay segments in seagrass recovery. The lack of seagrasses north of the Courtney Campbell has been documented since 1948. “We found that the abundance and density of seagrasses north of the causeway is directly related to how far away the area is from open water,” Tomasko said.

The Tampa Bay Estuary Program calls Old Tampa Bay its “problem child” because of its persistent nutrient and circulation woes.

Seagrasses have been documented 13 times in the Rocky Point area north of the causeway but defined as “persistent” less than five times in the areas furthest away from tidal flows.

FDOT agreed to consider a bridge rather than additional stormwater ponds because the results will be more significant within the ecosystem – and significantly less expensive for taxpayers. “The FDOT is responsible for mitigating their impacts, so we didn’t conduct this study in a vaccuum,” Tomasko adds. “If we found a benefit was likely, that was fine, but they would have been fine if we hadn’t. We all know if the system doesn’t respond, they’ll have to do more.”

Tomasko points to successful seagrass recruitment in the Florida Keys after a causeway built by Henry Flager was replaced with a bridge in 2008. Re-opening the lake to tidal flows improved water quality and seagrass growth in about 200 to 300 acres, he said.

Closer to home, Pinellas County created an additional 100 acres of seagrasses by replacing part of the main causeway into Fort DeSoto Park with a bridge in 2004. The effort, partially funded through FDOT was so successful that a second causeway has been breached to allow tidal flow into another lagoon.

Many questions about the proposed bridge still remain but experts at a recent meeting of the Agency on Bay Management and TBEP Technical Advisory Committee support the concept in general.

“I’m all for it,” said Penny Hall, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute’s seagrass expert. “Ruppia doesn’t hold sediment in place because it only has a surface root system.”

“It does fit neatly into our focus area and I like the idea of looking at different ways to achieve those long-term goals,” adds Holly Greeening, executive director of the TBEP.

But as important as the results may be for the Rocky Point area, it may not become a trend in Tampa Bay, Tomasko said. “We can’t just assume a bridge is necessary, and I’m not sure that salinity is all that much a problem in other areas, even on the west side of the Courtney Campbell.”

[su_divider]