For centuries, scientists shared their research on paper or through letter exchanges. They didn’t have a choice, but it created bottlenecks in the advancement of knowledge.

Open science today, on the other hand, leverages technology to provide an improved framework for scientific discovery, collaboration and sharing. It’s transparent and accessible to any interested scientist – or policymaker or concerned resident.

“At the end of the day, applied science should provide guidance for environmental managers and policymakers,” says Marcus Beck, the newest scientist at the Tampa Bay Estuary Program. “Open science makes it much easier to provide the science that supports those decisions.”

The underpinnings of open science are based on the modern conveniences enjoyed through the advent of the internet – think networking, computer code, algorithms and apps. Though they might be intimidating for most people, the final products are readily accessible, documented and understandable, and updated as soon as new information becomes available.

Beck uses a platform called GitHub to host and share TBEP’s open science products. Like Linux, the open-source platform that powers most of the internet, Android phones and the world’s top 500 supercomputers, GitHub can enhance collaboration among scientists by sharing analysis and coding resources. “Working together makes us all more effective,” Beck said. “Everyone can see the source code and improve upon it.”

“Stoplight” Graphic First Product

“Stoplight” Graphic First Product

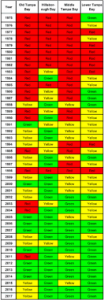

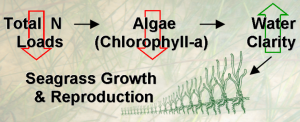

Take TBEP’s iconic “stoplight” graphic that’s been tracking changes in water quality since 1975. The original science that led to the “red-yellow-green” targets has historically only been available on scanned PDFs, so it’s difficult to access. Generating the graphic also requires many hours of mining massive databases and copying appropriate statistics into a complex formula on an annual basis.

Recreating that report using an open science platform is Beck’s first proof of concept to demonstrate the benefits of open science. The methodology that led to water quality targets that allow seagrasses to grow is clearly identified as part of the source code in the new platform.

Additionally, the new open science platform automatically checks appropriate databases daily. In this case, it’s the 45 sampling stations operated by the Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County (EPC). If something changes, it plugs the new data into the report so results show up immediately.

More Data, More Quickly

Stakeholders – both scientists and policymakers – will soon be able to access a dashboard that is updated as new data are posted. That could make a difference in places like Old Tampa Bay, the only bay segment that doesn’t consistently earn a green light on the stoplight graphic. A large part of the problem is the Pyrodinium blooms that could block sunlight from reaching seagrasses nearly every summer. Quickly synthesizing and reporting water quality data during months when Pyrodinium is or is not blooming could help scientists address other issues in the beleaguered bay segment.

Stakeholders – both scientists and policymakers – will soon be able to access a dashboard that is updated as new data are posted. That could make a difference in places like Old Tampa Bay, the only bay segment that doesn’t consistently earn a green light on the stoplight graphic. A large part of the problem is the Pyrodinium blooms that could block sunlight from reaching seagrasses nearly every summer. Quickly synthesizing and reporting water quality data during months when Pyrodinium is or is not blooming could help scientists address other issues in the beleaguered bay segment.

The dashboard also provides summaries of phytoplankton or algal species, as they are observed, providing managers a quick synopsis of change as blooms unfold.

“Using the online dashboard to link the water quality outcomes with actual cell count data provides more timely and informed way to look at potentially harmful algal blooms,” Beck said. “It identifies specific species as they occur and shows how they relate to the water quality report outcomes.”

Up next are dashboards for tidal tributaries as well as fish and benthos — the creatures who live on the bay bottom and form the basis of the food web.

Benefits for All

Beck met Ed Sherwood, TBEP’s executive director, at a 2017 workshop on open science funded through the National Academies of Science. “It was a real eye-opener,” Sherwood said. “We’ve applied our science-based management approach in a very traditional way in Tampa Bay, but this new approach provides an accelerated, more efficient process. We’re breaking down institutional silos and broadening collaborations as we work toward the same goal — sustaining, enhancing and accelerating Tampa Bay’s recovery.”

Beck met Ed Sherwood, TBEP’s executive director, at a 2017 workshop on open science funded through the National Academies of Science. “It was a real eye-opener,” Sherwood said. “We’ve applied our science-based management approach in a very traditional way in Tampa Bay, but this new approach provides an accelerated, more efficient process. We’re breaking down institutional silos and broadening collaborations as we work toward the same goal — sustaining, enhancing and accelerating Tampa Bay’s recovery.”

Most researchers welcome the opportunity to work more effectively with their peers, although some are still a little leery. “It’s a totally different way to work,” Beck points out. “People have a lot of time and money invested in their research and they don’t want to give a leg up to their competitors. I think that once they see that sharing their science makes it better and more efficient, they will want to be part of the process.”