COVERING TAMPA BAY AND ITS WATERSHED |

Our subscribe page has moved! Please visit baysoundings.com/subscribe to submit your subscription request. |

||||||

|

The Sea Folk: A Definitive History In many ways Gulfport, a small community on the shores of Boca Ciega Bay, is a microcosm of development along Tampa Bay. A fascinating new book by historian Lynne Brown details the growth of the city from its first founders through the early 1920s. This excerpt describes the challenges facing fisher-folk in the late nineteenth century. We read in many historic sources that H. B. Plant, the man who brought the railroad to Tampa, effectively wished that Pinellas would never become much more, as St. Petersburg historian Raymond Arsenault wrote, than "a refuge for weekend excursionists, mullet fishermen, and a few foolhardy citrus farmers." Plant was well on his way to realizing that goal in the 1890s, for fishing in Pinellas and certainly in Disston City (which later became the city of Gulfport) was truly the only remaining vocation available to residents. The expertise of the locals as fishing and hunting guides was well known and promoted, even by Plant himself, at his elegant Tampa hotel. But scratching a living from the Gulf and the bay was not, and never had been, an easy or profitable life. Foremost of the difficulties was the process of getting a catch to market. Now, however, two new factors had improved the fisherman's options: the railroad, of course, and the arrival of Henry W. Hibbs' fish company in St. Petersburg. Hibbs brought his fish business to St. Petersburg from Tampa in 1889 and opened a fish house on the Orange Belt Railroad pier to offer locals an outlet for the sale of their catches. No longer did they have to contend with shipping by boat or rail to Tampa or even more distant markets. They responded enthusiastically, with about 1000 pounds a day brought in for processing, which by the end of the century had become 10,000 pounds or more. The locals trusted Henry Hibbs, for they knew him and he knew them all. He gave them credit when they needed it and paid them fairly and promptly. He also tried to keep up with every possible modern improvement, as in the matter of providing ice for shipments. At first he had relied on ice brought in by the railroad, never a particularly dependable method, but soon he built his own ice plant near the foot of the half-mile long St. Petersburg pier. He overcame the problem of transporting the ice to the end of the pier by constructing what amounted to a wheeled platform rigged with sails, which was used successfully for many years and only abandoned after it ran down and killed a tourist in 1913. Sometimes enterprising locals made a little more by selling directly to Point residents through the simple method of catching ten or a dozen, spiking them onto a palmetto frond, and going house to house offering them for five cents apiece, a considerable advance over Hibbs' price, but obviously not practical for dealing in quantity. When there was some slack time, most fishermen turned to building their boats, particularly the little skiffs used in mullet fishing. Of course, some became extremely proficient at the trade and ended up as professional boat builders. But the homemade skiffs were the backbone of the local industry. These were small flat-bottomed boats designed for use with oars in shallow water. They were usually about 16 feet long, with a bow cap on them and a net table in the rear, for loading the several hundred yards of net carried on each. The oars, too, were fashioned by the men who used them, 14- to 18-foot sections of 2 x 4 or 2 x 6 whittled down to a four-foot blade on one end and a handle the rest of the way up. With no other form of propulsion, the skiff was poled along through shallow water, and paddled through the deeper parts of the bay, heavy hard work indeed.

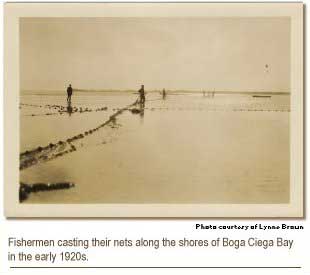

So fishing was often the only way to avoid starvation, even to make a few dollars. Almost every man and boy in Disston City, and well into early Gulfport, was at least a part-time fisherman ö when the mullet were running. Each month of the year brought a different kind of catch. Amberjack and sheepshead ran in January and February; grouper and trout from November through March; bass, mackerel, and kingfish spring and fall. Flounder, jewfish, redfish, shark and snook put in occasional appearances, and the king of gamefish, the tarpon, was in season from May through the summer. And then there were the mullet, which were taken all year, except between November 15 and January 1, the spawning season. Much of the netting was done right along the beaches. Nathan White, grandson of pioneer Joshua White, described some of the process: "The seining of mullet was done up and down the beaches, but they didn't go offshore for that ö you'd take the mullet and if you'd have a good northwester in November or December, it would drive these spawned fish out into the Gulf. "The fishermen would then haul and seine them on the beach. They would put one end on the beach and make a big half moon circle out to the gulf and come back, and wrap the net around the post and pull the net in going up the beach. It was unbelievable the amount of fish they pulled up onto the beach." That, of course, was during the days when it was said there were so many mullet in the bay that they made a roaring noise when a whole school of them crossed a sandbar. It has long since been against the law to put one end of a net on land. Joe Roberts made mullet a livelihood and he knew them well. "The mullet is a migrating fish, and if he takes a notion to go to Sarasota, it don't take him very long to get there.ä Mullet roe, he added, "is as good as caviar. Is, in fact, caviar." They also did some netting away from the beach, making a cradle with the net and roping the fish within. In some ways, the very abundance of the bay worked against those who depended on it for livelihood. The huge catches, particularly as the season wore on, drove the prices down to almost nothing, perhaps a penny or two a pound. Walter Roberts recalled, ãI once saw my father catch 500 mullet with a cast net in little more than an hour. The fish averaged two pounds each, and one cast of the net would bring in 15 or 20 mullet.ä Lynne Brown, a resident of Gulfport since 1978, earned a journalism degree from Boston University. She was the founding chair of the Gulfport Historic Preservation Committee, a director and curator of the Gulfport Historical Society Museum and served on the Gulfport City Council for four years, including a term as vice mayor. Brown also is the author of "Gulfport: Images of America." Excerpted with permission from Gulfport: A Definitive History, published by The History Press |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

© 2004 Bay Soundings

|

|||||||

The grassy flats to the west of the settlement, which early on acquired the nickname "Fiddlers' Flats," were a good source of shellfish. Clams, stone crabs, oysters, coquinas (found in the Gulf, not the bay), scallops and so forth were neither plentiful nor meaty enough to provide a diet staple, but they added a different taste now and then, as did the meat of the turtle. Now illegal, turtling excursions had been a feature of this coast for decades if not centuries. Moonlight nights on Blind Pass provided occasions for party-like trips after the big ones, the 600- to 700-pounders.

The grassy flats to the west of the settlement, which early on acquired the nickname "Fiddlers' Flats," were a good source of shellfish. Clams, stone crabs, oysters, coquinas (found in the Gulf, not the bay), scallops and so forth were neither plentiful nor meaty enough to provide a diet staple, but they added a different taste now and then, as did the meat of the turtle. Now illegal, turtling excursions had been a feature of this coast for decades if not centuries. Moonlight nights on Blind Pass provided occasions for party-like trips after the big ones, the 600- to 700-pounders.