COVERING TAMPA BAY AND ITS WATERSHED |

Our subscribe page has moved! Please visit baysoundings.com/subscribe to submit your subscription request. |

|||||||

|

||||||||

|

Chesapeake Bay: This is the first in an occasional series of articles spotlighting restoration efforts in estuaries along the Atlantic coast. Oyster restoration in Tampa Bay was first profiled in Bay Soundings last fall (see Joy of Oysters).

And while support for oyster restoration is strong, advocates differ on the best way to proceed. One course is to scale up efforts to supplement the native strain, Crassostrea virginica. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation is one of several interests backing the establishment of oyster reef sanctuaries designed to lure baby oysters from the wild, coupled with stock enhancement using genetically superior, hatchery-raised oyster spat. Meanwhile, pressure is mounting for large-scale introduction of disease-resistant Asian oysters. The proposal is gaining favor with many commercial fishermen and Maryland officials who say that diseases present in the bay make it impossible to restore a sustainable native oyster fishery. Hardier Asian oysters are fast-growing and appear to have a higher disease tolerance and much lower mortality - 5-10% from all causes versus 80-90% on average in higher salinities for their native counterparts. That proposal alarms many scientists and environmentalists who argue that efforts to create self-sustaining native oyster populations shouldn't be abandoned until they are scaled up appropriately. "Scale is critical," says Bill Goldsborough of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. "We can't begin to judge the success of native oyster restoration until we've given it all we've got at a big enough scale." Over the past 10 years, the foundation has worked with state and federal agencies and university partners to create about 50 large reef sanctuaries plus numerous smaller ones. But the greatest successes occurred after 1998, when shell piles began being stocked with disease-tolerant oysters. Those efforts have helped rekindle small populations of native oysters in the vicinity of the sanctuary reefs. The goal is to increase the native population ten-fold over 1994 levels by 2010, with modest gains in early years followed by exponential increases as efforts ramp up. The foundation grows between 700,000 and 1 million oysters a year at its farm on Gloucester Point using a disease-resistant strain called DEBY, which was developed from native oysters at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS). DEBY has demonstrated tolerance to MSX and Dermo, the two disease-causing parasites that helped whittle the bay's native oyster population to just 1% of historic levels.

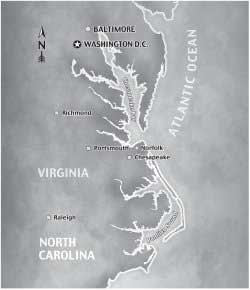

NAS weighs in A highly anticipated National Academy of Sciences report released last August on the risks and benefits of introducing non-native oysters to Chesapeake Bay bolsters the long-term research strategy of researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. The academy says carefully regulated aquaculture of sterile Asian oysters could help the oyster industry and generate needed risk-assessment data, whereas any introduction of a reproductive population of the non-native oyster should be delayed until more is known about the environmental risks. To learn more about the non-native oyster research at VIMS, visit www.vims.edu/abc. Bombing begins Eager to capitalize on successes in smaller tributaries, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recently mounted a multi-million dollar campaign to "carpet bomb" entire regions of the bay with the disease-resistant native oyster. While federal funding will dictate the pace of the project, Congress already has authorized $20 million for the Corps to begin helping Virginia and Maryland restore their native oyster, a task that could cost $500 million to complete baywide. While researchers expect heavy casualties at first, the plan is to continue smothering new reefs with the DEBY oysters until enough disease-tolerant oysters survive to create a self-sustaining population. Annual crops of baby seed oysters could then be harvested for restocking elsewhere around the bay. Meanwhile, researchers are forging ahead with studies to determine the environmental impact of introducing breeding Asian oysters. In one controlled experiment, scientists with VIMS introduced a million sterile Asian oysters into Virginia bay waters last fall. According to the Virginia Seafood Council, sponsor of the study, the shellfish are growing three times faster than native oysters and should be ready to harvest in the spring. VIMS is also partnering with the University of Maryland to monitor the growth and survival of another 5,200 lab-bred sterile Asian oysters in cages at several drop sites in the bay. Adding fuel to the debate, a new killer parasite has been discovered in North Carolina, where similar trials are underway. Called Bonamia, the parasite was found in Asian oysters taken from Bogue Sound near Morehead City, the first such recording in the mid-Atlantic states. Researchers tested oysters from the same spawn that are part of the Virginia Seafood Council trials in Chesapeake Bay but found no evidence of the parasite. Its origins remain a mystery. One theory is that Bonamia may thrive in the saltier Bogue Sound but cannot withstand the relatively low salinity of the Chesapeake Bay. Bonamia does not appear to be a threat to the native Eastern oyster. Last nail in coffin While disease is the dominant factor today, Goldsborough says the Chesapeake's famed oyster grounds have endured a triple whammy. Oyster dredging in the latter half of the 19th century knocked back the bay's massive 30- to 50-foot high reefs. The flatter reefs left behind were much more susceptible to smothering silt and sediments. Disease was simply the last nail in the coffin - starting in the 1950s with the introduction of the foreign MSX parasite and followed by the native Dermo parasite in the 1980s. Just how significant is the Chesapeake Bay's oyster fishery? While it peaked more than a century ago, oysters remained the bay's most valuable fishery until the 1980s when watermen reaped an annual harvest of roughly 2 million bushels with a dockside value of $30 million. Landings plunged to an all-time low of 20,000 to 25,000 bushels in 2003. But oysters are prized for more than their meat. Oyster reefs rival coral reefs in the abundance of marine life they support, and the bivalves are highly efficient filter feeders capable of scrubbing impurities from the water. In 1870, there were enough oysters in the Chesapeake to filter a volume of water equivalent to the entire bay in just three to four days. Today, it would take over a year for oysters remaining in the Chesapeake to filter the same volume of water. Pamlico Sound: Less than 150 miles south of the Chesapeake, Pamlico Sound cuts a massive swath between coastal North Carolina and the Outer Banks. Historical accounts suggest most of the sound was once fringed by extensive oyster reefs, although signs of over harvesting were evident by 1900. Today, experts question whether there are enough oysters left to initiate a recovery. "The situation is pretty grim," says Jeff DeBlieu of North Carolina's Nature Conservancy, which is spearheading oyster reef restoration in the Sound. "As far as I can tell, we don't have any healthy wild oyster reefs. All we have are remnants," says DeBlieu of the "put-and-take oyster fishery" that has emerged in the absence of any real restoration. The Nature Conservancy hopes to change that with a coordinated effort to build oyster reefs and have them set aside as sanctuaries. Five sanctuaries have been established so far, and efforts are expected to accelerate in April when a state-financed hatchery comes online. The hatchery at Carteret Community College will raise native oysters from wild brood stock to produce a genetically diverse strain that will be used to populate reefs. Plans are also underway to establish a community oyster gardening program with seed stock from the hatchery. While no formal goal has been established, the North Carolina Coastal Federation is organizing a group to develop a restoration plan. DeBlieu believes more than 100 sanctuaries may be warranted in the million-acre estuary. Getting to critical mass quickly will be important. While large-scale restoration may be a tough sell, DeBlieu says, it has to happen at sufficient scale or it simply won't work. "You're going to lose oysters to predators and disease, and if you've only got a million to start and you lose 90% it's tough to make it through the bottleneck." "You're doubly damned because some people will say we've been trying to do restoration in Pamlico Sound for 25 years and it's failed. But all we've done is put and take - build an oyster reef, wait a few years, then harvest it all out. Until we have a system of undisturbed sanctuaries and we can advance at a meaningful scale we won't have true restoration."

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

© 2004 Bay Soundings

|

||||||||

Decades of over-harvesting and disease have decimated America's oyster fisheries, but nowhere has the decline gripped the cultural psyche more than in the mighty Chesapeake where reverence for oysters is passed down from generation to generation like fine china.

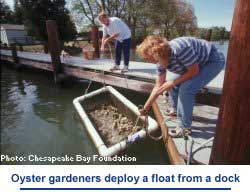

Decades of over-harvesting and disease have decimated America's oyster fisheries, but nowhere has the decline gripped the cultural psyche more than in the mighty Chesapeake where reverence for oysters is passed down from generation to generation like fine china. The foundation also has recruited over 1,000 citizen 'oyster gardeners' to grow native oysters in cages suspended off docks for reef restoration and research.

The foundation also has recruited over 1,000 citizen 'oyster gardeners' to grow native oysters in cages suspended off docks for reef restoration and research.