|

||||||||

Story and art by Sigrid Tidmore

Artwork: Sigrid Tidmore. www.SigridTidmore.com

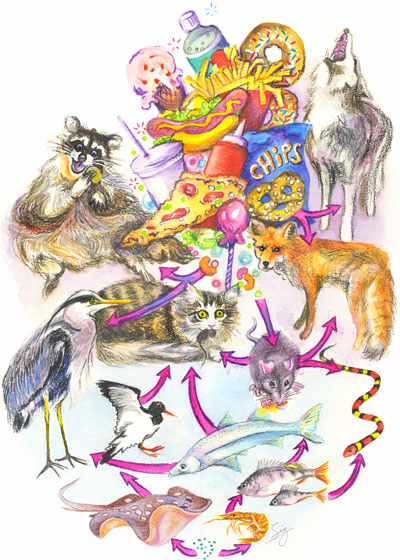

FAST FOOD WEB — what partiers leave behind on the beach is changing the diets of animals in our native food web.

If you're reading Bay Soundings, chances are you're already trying to be a good steward of our environment. But listen up — because many of the small things we all do unconsciously can cause unintentional, long-term damage to animal populations, particularly those that are already endangered. Just a momentary lapse can disrupt the delicate balance in our favorite preservation areas.

Remember learning about food chains? Today environmental scientists talk in terms of the "food web" — a complex interaction of sunlight, microbes, plants, prey and predators exchanging energy at many different levels simultaneously. We now know that seemingly small changes in one habitat can have dramatic effects on species far upstream on the web.

For instance, we've all seen fishermen navigating their boats through shallow bay waters where their props dredge up the muddy bottom. Short-term, that raises turbidity so less light reaches the sea grasses and they grow less abundantly. Less grass means less shelter for juvenile grouper, and the next season the fish are fewer.

Longer-term implications are even more severe for fish and the sportsmen seeking them. Richard Sullivan, preserve manager at Cockroach Bay in Hillsborough County, has observed thousands of prop scars that have destroyed whole sections of seagrass beds that likely will never grow back. The tidal action sweeps the prop scars clean, creating a rut that will impact fish populations for years to come. And it all started with just a little careless boating fun.

PARTY ANIMALS

Photo Courtesy Christina Evans, ChromaGraphics Studios

A Ft. DeSoto raccoon drops into his favorite fast food restaurant.

Tampa Bay has a well-earned reputation for having beautiful beaches, but it comes at a price. According to Ft. DeSoto's Park Supervisor Jim Wilson, a three-day holiday weekend can attract as many as 120,000 visitors. They will leave some 600 trash cans brimming with 40 tons of trash. That doesn't count the food waste, bottle tops, cigarette butts, rubber bands and assorted personal items left scattered around.

Now try imagining "the night after" from a raccoon's point of view.

Even though the clean-up crews hit the beach at dawn the next morning, the nights following big holiday parties must feel like a Las Vegas buffet to the local wildlife opportunists. This junk food fest used to be easier to manage when the park had 68 workers, but with budget cuts, everything is now done by a crew of 28, which makes clean-up a slower process.

At the same time, raccoons are being forced into parks and preserves as their home ranges are being reduced. As anyone who has ever lived near a raccoon will attest, they leave trails of destruction wherever they go. People are not tolerant of these food bandits living in their neighborhoods, so they end up congregating in our nature preserves.

Raccoons are notoriously omnivorous scavengers with an excellent sense of smell. Studies that compare the density of opportunistic species show greatly increased populations in picnic areas versus pristine natural areas. What are they eating? You guessed it. Raccoon autopsies reveal that human junk food accounts for a significant portion of their diet. Think about that next time you see a fat raccoon.

While the state's total population of raccoons has not increased, their density has grown significantly in these parkland "ghettos," where continued population growth is limited only by the availability of food. In addition to picnic refuse, these ravenous creatures supplement their natural diet of crabs and shellfish with the eggs of turtles and ground-nesting seabirds.

Our wasteful food habits are changing the food web in other ways as well. Common house mice and the black rat are among history's most notorious human companions. They compete aggressively with the naturally occurring Sanibel rice rats — a gentle, little creature that creates softball-sized nests among the marsh reeds. Additionally, a booming population of invasive rodents attracts red and grey foxes and the common coyote.

Community Guidelines for Discouraging Coyotes & Raccoons

-

Avoid feeding pets outside. If outside feeding is necessary, remove food and water bowls

as soon as your pet has finished eating. -

Keep bird feeders high and out of reach.

-

Remove the fruit falling from your trees on a daily basis. You may need to dispose of meat and fish scraps in

closed bins. -

Keep all trash in high-quality containers with tightly closing lids. Freeze particularly fragrant refuse until your trash pick-up day.

-

Keep your dogs, particularly small ones, on a leash and do not allow them to freeroam. They could end up as coyote fast food.

It's important to note that raccoons, coyotes, skunks, foxes and other carnivorous mammals are susceptible to rabies. Be sure to report any suspicious behavior to animal control authorities.

The absence of natural apex predators such as panthers and red wolves has contributed to the marked increase in coyotes throughout Florida. As early as 1998, studies showed coyote populations were up to 13% more dense near beach areas. Coyotes are found in every Florida county from the northern border to the southern mangroves where fiddler crabs hide among the mangrove roots. Coyotes eat fiddler crabs, but they also love mice and rats, and will cheerfully attack a bag of ripe, abandoned garbage.

Coyotes snuck into Pinellas County about 20 years ago, but it wasn't until recently that sightings were documented in Ft. DeSoto Park. Unlike humans, coyotes seldom overpopulate their home area. When food gets scarce females produce smaller litters. However, judging by the increase in coyote sightings, there's been plenty of opportunity to grow their litters on the junk food habit.

Scientists note that the primary reason for the growing number of scavengers is our own careless housekeeping. Simply tossing a half-eaten chicken bone into a bush is an open invitation to a rat, raccoon or hungry coyote.

And that's before taking into account what happens when we carelessly dispose of other trash. Innocuous small pieces of plastic like balloons, empty bags or hair bands can constrict the digestive systems of animals that accidentally consume them, or toxic refuse like chocolate and cigarette butts may be poisoning them.

I DON'T CARE HOW CUTE THEY ARE — DON'T FEED THE ANIMALS!

Reasons to NOT Feed the Wildlife

-

When young wild animals are taught to depend on a human-provided food source, they may not fully develop essential foraging skills.

-

Wild animals that are used to being fed by humans commonly lose their fear of people – an important survival trait. They may be harmed when their begging is misunderstood, harassed by dogs, or hit by cars.

-

The food humans usually feed to wild animals is not nutritionally complete, and it can cause serious health problems, especially when they are young and still developing.

-

A constant, human-provided food source may attract many more wild animals to the area than would normally be found there. Disease can spread much more quickly among animals when they gather artificially for food.

-

Reproduction rates may also be affected when an unnatural food source is readily available. Animals may produce too many young than what the area can support.

Visit any boat ramp where the anglers clean their catch, and you'll see a congregation of begging birds. Pelicans, herons and gulls — it seems so harmless to toss them the miscellaneous fish parts.

But Cameron Guenther, a research scientist for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, warns that an innocent fish skeleton causes both long- and short-term problems.

"While the impulse to feed these funny creatures is strong, the result is that grown birds become inefficient and lazy predators. Weak birds aren't eliminated from the gene pool and most troubling, the birds become overly socialized towards humans. They'll swallow any catch anywhere — hook, line and sinker."

It's not uncommon to find a "pet" blue heron roaming around local beaches or motel pools begging for hot dogs. Many people enjoy feeding wildlife because it allows them to have close contact with the animals, or they feel they are helping them survive. But experience shows that it almost always leads to problems for both the animals and humans.

Most conscientious fishermen know not to feed the wild dolphins. However, in an odd twist of unintended consequences, there is now some anecdotal evidence that dolphins follow sport fishermen as they play deep sea fish to the point of submission. When the fishermen release their exhausted prey, the tired fish becomes an easy catch for the clever dolphins. Unfortunately, it's another example of how our play may be penalizing an important animal species.

OUR PET PREDATORS

Camouflaged eggs are barely visible in this oystercatcher ground nest.

Sometimes it is actually the animal lovers that inadvertently cause wild animals distress. Our domesticated pets belong in our homes and under our control. When they are allowed to roam in the wild, they quickly follow their natural instincts and become destructive.

"House cats are the greatest threat to small mammals along our beaches," says Melissa Tucker, a specialist in species conservation planning with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. "One feral cat can wipe out fauna in an entire dune system, including ground-nesting birds, mice and even the plentiful Eastern cottontail rabbit."

Studies done in northwest Florida showed that beach mice populations were severely impacted in dune habitats located near residential areas. Tracks of house cats correlated with the total elimination of the mice in seven of the 21 areas being monitored over a year's time.

The American Bird Conservancy estimates that millions of shorebirds are killed annually by cats and they are running a campaign to educate pet owners to make their kitties inside pets. Ironically, many of us who love birds put out feeders to attract them, never realizing we are placing them in danger of our free-roaming housecat.

The primary challenge for dog lovers is keeping their pets under control in estuary and beach areas. Nearly every preserve manager has seen the inadvertent damage created by frolicking dogs who were allowed to run off-leash in bird-nesting areas.

"They just don't see what they're stepping on," says Richard Sullivan of Cockroach Bay. "I know what oystercatcher nests look like, and even I have a problem stepping carefully over them." (See nest photo)

Even if the dog avoids stepping on the nest, being disturbed is a traumatic event for a shorebird. When parents are chased off their nests, eggs may bake in the summer's heat and the chicks may die of exposure or become a meal for other predatory birds. Many times, the birds that a dog playfully chases down the beach are resting after very long flights — perhaps thousands of miles. When boaters innocently take their pets with them to isolated barrier islands or rookery areas, they create havoc among the flock that will last long after they've gone home.

Bird populations are under stress from so many directions: habitat destruction, predation and disease. To further stress these greatly diminished species with our pets' play may be all it takes to push them out of the food web and into extinction.

(Read more about beach bird conservation efforts in this issue.)

THE TRUTH ABOUT NIGHT LIGHTS

Light pollution is a hard concept to tackle because most people believe that light is benign. After all, what difference does one light make outside by the pool? As it turns out — LOTS!

The introduction of artificial light into wildlife habitats represents a profound encroachment, particularly in coastal areas. There has been a great deal of attention focused on the altered behavior of sea turtles during nesting and hatchling dispersal — and most areas now require less invasive low pressure sodium vapor lights where turtles are likely to nest.

However, there are less publicized, but equally disruptive effects of night lighting on beach communities. Many small species experience a disruption of foraging behavior due to their increased fear of predation. In the humble beach mouse, for instance, scientists have shown that lighting disrupts their circadian clock, changes hormone production and renders them less able to hunt for food. Many small animals feed less during full moons to avoid being seen by predators. When we light up our beaches, it's likely that a wide variety of prey species will become chronically underfed.

Other animals may become disoriented by artificial light because their eyes have rudimentary cone systems that do not adjust to glare. This is why so many creatures freeze in car headlights and become roadkill. Lighting can affect the navigation systems of migratory birds and even bats, causing them to fly widely off course.

Photo: Sigrid Tidmore

Light pollution can ward off the insects that pollinate night-blooming plants.

Moving lower down the food web, studies now suggest that light pollution around lakes and shores prevent zooplankton from eating surface algae, potentially boosting the algal blooms that kill off fish and lower water quality.

It has been documented that nighttime lights interfere with the ability of moths and other nocturnal insects to navigate. Many night-blooming flowers depend on these insects to pollinate them. In my own backyard, I have noticed that my night-blooming cactus no longer produce fruit after the flower falls off. This type of species decline in plants can change an area's fundamental long-term ecology — and all because we wanted another light for our patio.

TURN IT DOWN

No article about our beach playtime would be complete without mentioning music — or some might say — loud noise. Jet skis, motor boats, boom boxes and motorcycles — the racket we create in the name of fun has left many beach species disoriented and distressed.

Brandt Henningsen, chief environmental scientist at Southwest Florida Water Management District, tells a story that highlights the competing issues between our desire to play in nature and give nature back its independence.

Recently, 2500 acres of abandoned mines became the largest coastal restoration area to be planned in Tampa Bay. Known as the "Rock Ponds" it is being designed with both intertidal and coastal uplands — perfect for a productive bird rookery. You can imagine the preserve managers' surprise when a public user group petitioned the county commission to use the property as an airfield for flying model airplanes. The noisy engine sounds would have undone years of careful habitat restoration. Fortunately, in this case, another, more appropriate site was found, but this is exemplary of the kind of choice we are being asked to make more often: The right to use our green spaces versus leaving them in natural isolation.

WE HAVE MET THE ENEMY — COULD IT BE US?

As the old adage goes, too much of a good thing can turn bad. In some notable places, the onslaught of nature-loving visitors is steadily eroding the very ecosystems that ecotourism intends to protect. Visitors are trampling, polluting and gobbling up scarce resources in fragile habitats.

In a time when we find predators eating our junk food and native field mice unable to eat at all, we need to take a closer look at our activities. In the name of play and relaxation, we are over-using and under-appreciating what we have. The paradox is that only by publicizing the precious nature of our natural resources can we raise a wider awareness that could prevent its destruction.

We have a difficult dilemma: Learning to enjoy nature without interfering with it.

Bay Sounding readers — you are the ones who must set the example, spread the word, and herald in a more conscious play relationship with our precious natural environment. Share your thoughts and examples with us online by emailing editor@baysoundings.com.