COVERING TAMPA BAY AND ITS WATERSHED |

Our subscribe page has moved! Please visit baysoundings.com/subscribe to submit your subscription request. |

||||||||||

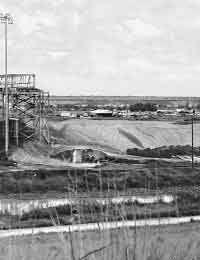

Don Tompkins has spent the better part of his life in the phosphate business, first in Houston with Mobil then in Florida working for Cargill, now Mosaic. "All our dads grew up working in the industry too," Tompkins says, with a southern drawl that exposes his Texas roots. Facility manager at Mosaic's Four Corners, Tompkins oversees a massive site with 400 employees, a phosphate beneficiation plant and $200-million annual operating budget. When it comes to pumping matrix, Four Corners dominates, moving 18,000 gallons of rock slurry per minute or 2500 tons an hour on average along miles of pipeline. The monthly electric tab alone is $3 million. Phosphate is a natural, non-renewable resource essential for all living things. About 90 percent of the phosphate processed in Florida is used to make fertilizer. The rest is used in animal feed supplements, and a variety of consumer products from toothpaste and soft drinks to light bulbs and bone china. The industry has deep roots in Florida, dating back to 1883 when phosphate rock was first discovered near Gainesville. Then came the "Great Florida Phosphate Boom" of the 1890s after high-grade deposits were found in Marion County and the Peace River. But the phosphate rush that brought hundreds of prospectors into the state was short-lived. Of 215 mining outfits operating statewide in 1894, only about 50 were left at the turn of the century after lesser contenders were weeded out. Today, there are just three phosphate mining companies left in Florida out of about 20 operating in the state two decades ago: Mosaic, largest by far with $4.7 billion in annual sales, created in 2004 with the merger of IMC Phosphates and Cargill Crop Nutrition; CF Industries; and PCS Phosphate in Northern Florida. A fourth company, U.S. Agri-Chemicals, processes fertilizer in Central Florida but does not mine here. "We're proud of what we do," says Tompkins, who lauds the industry's contributions and Mosaic's efforts to return the mined land to productive uses. Phosphate related-goods are the #1 export from the Port of Tampa and one of Florida's leading export commodities with a 2003 value of $1.3 billion. In 2001, the Port of Tampa reported that phosphate and sister industries created more than 41,000 jobs and an estimated $5.9 billion economic impact to the Tampa Bay region. Led by Florida, the U.S. accounted for 52 percent of the world trade of ammonium phosphate - one of the few bright spots in the nation's otherwise bleak national balance sheet on international trade.

But the industry is shrinking as it gets harder and costlier to mine for phosphate. "We used to go 15 feet down to get 30 feet of matrix," says Tompkins. Nowadays, companies have to dig through 30 feet of overburden to access 15 feet of matrix. It's a tough business getting tougher. Stealing a page from Cargill's spinoff of its fertilizer holdings last year, CF Industries announced plans in May to take its company public. While the Illinois-based fertilizer cooperative reported a $67 million profit in 2004, that followed five straight years of losses. In July, Mosaic announced plans for one of the largest permanent layoffs in recent industry history, with the closure of its Kingsford mine this September. After 40 years, the phosphate rock at Kingsford has been depleted. Closing the mine southwest of Mulberry will result in the layoff of about 275 workers. While employees may be considered for vacancies in other Mosaic operations, how many will be absorbed is unknown. After The Phosphate Rush While it's no secret that Florida's phosphate supplies will eventually run out, or reach a point when mining is no longer economically viable, "the issue hasn't hit the radar screen yet," says Gray Gordon, vice president of Mosaic. That is despite the fact that Florida phosphate supplies three-quarters of U.S. fertilizer needs, that domestically produced fertilizer keeps food prices low, and that phosphate's economic impact to the Tampa Bay region and Florida is sizeable.

What happens when phosphate reserves dry up and the industry departs? No one's talking about it. Thirty years from now, phosphate reserves in Florida, which contain the country's richest mineable ore, may be exhausted. The issue is not only one of economics, but of future land use and the productivity of reclaimed mine lands left behind. After contacting the U.S. Department of Agriculture and House Committees to inquire about any efforts to discuss and address dwindling U.S. reserves, Congressman Jim Davis says it appears to be receiving scant attention. "Florida's phosphate industry is an important player in Tampa Bay's economy and the state as a whole, so the questions raised are important here at home as well as on a national scale," said Davis in a statement through his press secretary. "What are we going to be left with after they go?" asks Charlotte County Commissioner Adam Cummings. "We should develop a good exit strategy. The industry needs to have a plan for their shareholders, the people of the state of Florida - and so do we." |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

© 2005 Bay Soundings

|

|||||||||||