|

||||||||

|

To Save Water Year-Round, Pricing Must Change [COMMENTARY]

|

By Victoria Parsons

In 1966, when the Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority broke ground on the largest desalination plant ever built, the world was a different place. Water was obviously valuable to residents of the island chain, but fuel was still cheap and abundant. Gas cost less than 25 cents a gallon, so the desal plant literally distilled fresh water from the sea, boiling it to capture steam that cooled back into water.

Today, fuel efficiency is a given from both a cost and an environmental perspective, but the true value of water is only beginning to come into its own. Betting that water is the new oil, Texas wildcatter T. Boone Pickens bought the rights to billions of gallons he expects to sell for an estimated $165 million per year. On an international level, some experts predict that nearly half of the world’s population will face severe water shortages in the next 30 years.

The Tampa Bay region, of course, has long recognized the limitations of cheap, easily available water. The so-called water wars of the late 1990s made it clear that the region’s rivers and aquifers could not provide an

unlimited source of water for its booming population and an ever-increasing need for water. The creation of Tampa Bay Water in 1998 allowed for ongoing investments in diversified sources, including the Tampa Bay desal plant, a 15-billion gallon reservoir, and reclaimed water for irrigation. The best-laid plans, however, faltered in the face of unexplained leaks in the reservoir and a three-year drought.

Conserving water has become a front-page story for daily newspapers as managers enforce the most stringent water restrictions ever, including a total ban on sprinklers in the City of Tampa because its reservoir on the Hillsborough River is nearly dry.

With water this cheap, why conserve?

One conservation tool that may not have been used as effectively as possible is pricing. Most utilities in the Tampa Bay region use what they call an inverted block rate structure that sets the price for basic service as low as possible with prices going up as volume increases. “It’s the opposite of the old volume discount where the price is lower for the best customers,” notes David Bracciano, demand management coordinator for Tampa Bay Water.

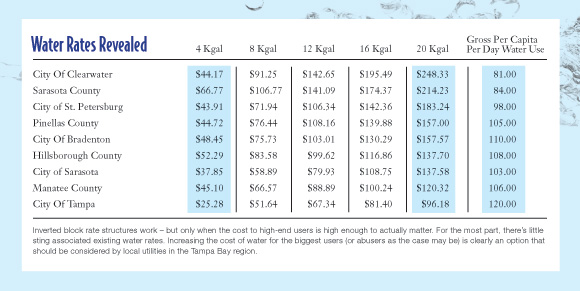

Nevertheless, the price of water for a homeowner using 20,000 gallons of water a month in the bay area is still dirt cheap – an average of just $150 per month.

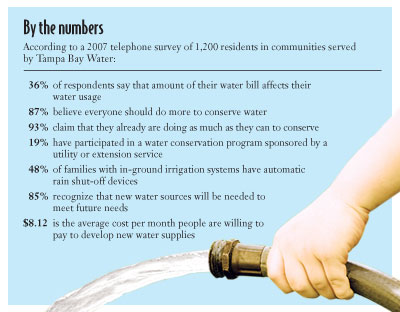

A 2005 study by four water management districts across the state compared the price of water with the per capita use. Not surprisingly, water usage dropped – in some cases dramatically – as prices increased. Along with water consumption and pricing, the report tracked family profiles because wealthier households use more water. (See chart)

|

Households at the bottom and top of the economic spectrum were less likely to be impacted by prices than those in the middle – identified as Profiles 2 and 3 and defined as owning a home valued at more than 25% but less than 90% of the average assessed value. The largest change came from Profile 3 households, where daily use declined from about 250 gallons per day per capita to about 65 as the price of water went from less than $2 per thousand gallons to more than $9.

Most Tampa Bay utilities already have inverted block rate structures, notes Jay Yingling, a senior economist in SWFWMD’s planning department and current president of the American Water Resources Association Florida Section. Pinellas County is an exception to that rule, because it charges an excess use surcharge when water use goes over 25% of the historic use.

“That’s fine and dandy, but what about the person with a quarter-acre lot who consistently uses a million gallons a month,” he asks rhetorically. “It’s consistent use but it never runs 25% over their historic use, so they’ll never see a surcharge.”

Tiers Work in Clearwater and Sarasota

As part of the 2005 study, the four districts created a model available to utilities to maximize conservation and main revenues. Yingling doesn’t know how many Tampa Bay utilities have used the free program, but pulling data from two recent SWFWMD reports makes it clear that the steeper the curve, the higher the saving.

The City of Clearwater, for instance, has one of the lowest costs in the region for the first 4000 gallons of water used monthly, but among the highest cost for households that use more than 20,000 gallons per month. The City of Tampa, which is still primarily dependent upon relatively inexpensive surface water, has the lowest cost at both extremes. Gross per capita water use is just 81 gallons per day in Clearwater, but 120 gpd in Tampa.

|

While the price has changed, the rate structure has been the same for the past 80 years, notes Jim Geary, director of customer service for the City of Clearwater. “We get some push-back on rates from people but we haven’t experienced that much lately with the drought going on,” Geary said. “Some people feel our rates are too high, but water is something that’s going to get more and more expensive – it’s not just the cost of water, it’s the environmental impact.”

Further south, Sarasota County per capita use has dropped from about 150 to 82 gallons per day as a new tiered-rate structure has been implemented. It’s both a function of pricing, says County Commission Shannon Straub, as well as stringent regulations that require low-flow plumbing, Florida-friendly landscaping and once-a-week watering restrictions even after the last drought ended. It probably helps that the county posts the names and addresses of the utility’s top 100 users on their website.

“Media kept asking us to provide it every year, so we decided to publish it online,” she says.

The price of water jumps from $2.32 for the first 4,000 gallons to $11.73 for households that use more than 18,000 gallons, a conscious decision on the part of the commission to encourage conservation. “People who are abusing water should be paying more,” she said. The utility also tracks water use closely and occasionally calls people to check that they’re refilling their pool, for instance, instead of losing water through an undetected leak.

“We get some flack, but it’s not a big issue,” she said. “Even with large families, we tell them to make their teenagers shower for five minutes instead of 10.” Landscape codes passed in 1997 with the support of a progressive homebuilders association limit the amount of turf so not ending the once-a-week water restrictions after the last drought ended wasn’t greeted with cries of outrage.

There is a better way

Recent calls for drought surcharges recognize the value of water at a time when it’s not falling from the sky, but rethinking tiered rate structures across the board makes more sense to us. If households can save 40% or more water year in and year out, that will go much further in minimizing the impact of the next drought than increasing water bills when the well runs dry.

|