|

||||||||

|

St. Pete Passes State’s Strongest Fertilizer Ordinance

By Victoria Parsons

A round of applause from a standing-room-only crowd marked the passage of the state’s toughest fertilizer ordinance by the St. Petersburg City Council in March. Supporters ranged from the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and Sierra Club to the Gulf Fisherman’s Association, Dolphin Landings Charter Boat Center, Sweetwater Kayaking and Wilcox Nursery.

“It wasn’t just the environmental ‘tree-huggers’ supporting this, there are a lot of different businesses who recognize that residential fertilizer is a major player in coastal pollution,” said Phil Compton, regional representative of the Sierra Club.

CORRECTION: |

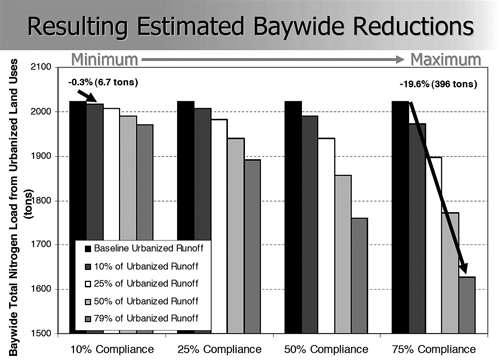

The St. Petersburg ordinance is based upon a model developed last year by the Tampa Bay Estuary Program working with stakeholders from across the region. The City of Gulfport passed a similar ordinance earlier this year and other governments, including Hillsborough, Pinellas and Manatee counties, are planning to take up the issue later this year. The TBEP estimates that 84 tons of nitrogen could be eliminated if all governments in the region passed similar ordinances and half of the residents complied.

“Most people are much more knowledge-able about the environment than we give them credit for,” said St. Petersburg Councilman James Bennett, who proposed the ordinance. “They’re really anxious to do something that makes a difference — if they can possibly help to stop 84 tons of nitrogen from flowing into the bay, they’re ready to jump on it.”

The centerpiece of the city’s ordinance is a ban on the use of fertilizer containing nitrogen during the summer rainy season when excess nutrients can be washed away in stormwater. Excess nutrients fuel the growth of algae that blocks sunlight and consumes oxygen other species need to survive. About 20% of the nitrogen loadings in Tampa Bay can be traced back to residential fertilizer.

Bennett, who has owned a lawn and landscape company for 26 years, pointed out most lawns in St. Petersburg are irrigated with reclaimed water that typically contains sufficient nitrogen and just needs a “summer blend” of iron and other micronutrients to keep grass growing well year-round.

The model ordinance will be considered later this year in Hillsborough, Pinellas and Manatee counties, with workshops scheduled for April in Hillsborough and Manatee counties.

Sarasota Leads the Way

When Sarasota County passed what was then the state’s strongest fertilizer ordinance in August 2007, some industry professionals predicted dire results if lawns went all summer without nitrogen. So far, that hasn’t happened, says Jack Merriam, environmental manager for integrated water resources.

Only one company requested a variance last summer, but when a horticultural agent looked at the site, it appeared to be overwatered not underfertilized, Merriam said. “We told them we’d be glad to consider a variance if leaf samples showed a nitrogen deficiency but we never heard back from them.”

Many industry leaders support the ordinance if a variance is available, notes George Pickhardt, owner of Arrow Environmental Services in Sarasota who holds a PhD in plant nutrition from Cornell. “Even before the ordinance passed, our standard protocol was not to use fertilizer within 15 feet of a body of water and we seldom applied nitrogen in the summer without a leaf sample that showed a deficiency, particularly in neighborhoods with reclaimed water,” he said.

While the Sarasota ordinance doesn’t currently contain a provision granting a variance with a tissue test, it is a priority for this year, along with continued education of retailers and residents, Merriam added.

|

Manatee Experiments with Reclaimed Water

Another priority in both Sarasota and Manatee counties is determining the level of nutrients in reclaimed water and then counting those nutrients as an integral part of annual fertilization plans. “We’d been using 100% reclaimed water on county properties but we had absolutely no clue as to how much nitrogen and phosphate was in that water,” said Rob Brown, senior environmental administrator in Manatee County.

The challenge with reclaimed water is that nutrient levels can vary depending upon which treatment plant it comes from. With county ball fields, it was relatively easy to track the amount of nutrients in reclaimed water at each location and then add supplemental fertilizer only when necessary, he said. “If we can show residents that those heavily used ball fields survive without additional fertilizer, they’ll be able to relate it to their own lawns.”

The long-term goal will be to blend reclaimed water to create a county-wide standard or to break down service areas so residents know what is in the water used in every neighborhood. “I think we’ll discover that either none or a very small amount of supplemental fertilizer will be needed.”

Learn more: |

Challenges Remain in Hillsborough, Pinellas Counties

Across Tampa Bay, local governments already are spending millions of dollars a year to build and maintain treatment plants that remove nutrients from stormwater — and that’s before more stringent regulations kick in. And as other sources are contained, residential fertilizer plays a larger role in the bay’s restoration. In some watersheds, such as Lake Tarpon, nearly 80% of the excess nutrients can be traced back to residential fertilizers.

Solving that dilemma will likely require intensive educational efforts coupled with regulations and a restriction on the sale of nitrogen-based fertilizer for lawns, notes Kelli Hammer-Levy, environmental program manager for Pinellas County water resources.

Education only goes so far, she said, just as early efforts to educate boaters about manatees showed that strict speed limits are necessary to protect the slow-moving mammals.

Some scientists, including turf experts at the University of Florida, question the wisdom of a summer ban on nitrogen because research shows that rapidly growing grass utilizes high levels of nutrients. Without enough nitrogen, they say, lawns may decline over time, increasing the potential for nutrient leaching and runoff.

“There are still some questions about the science, but in the meantime it’s better to err on the side of caution,” Hammer-Levy said. “Turf experts are focused on the optimum growth of grass, not the impact excess nutrients have in an ecosystem.”

Another challenge facing bay managers is enforcement, adds Tony D’Aquila, director of resource management at the Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County. “I can’t propose regulations that sound good but aren’t enforceable,” he said. “We need a mechanism to address non-compliance.”

The TBEP’s model ordinance forecasts a 50% compliance rate, based on results seen following a similar ordinance in Minnesota. That would prevent approximately 84 tons of nitrogen from entering Tampa Bay each year. If 75% of residents followed the recommendations in the model ordinance, nearly 400 tons of nitrogen would be removed – representing nearly 20% of the bay’s total loadings.