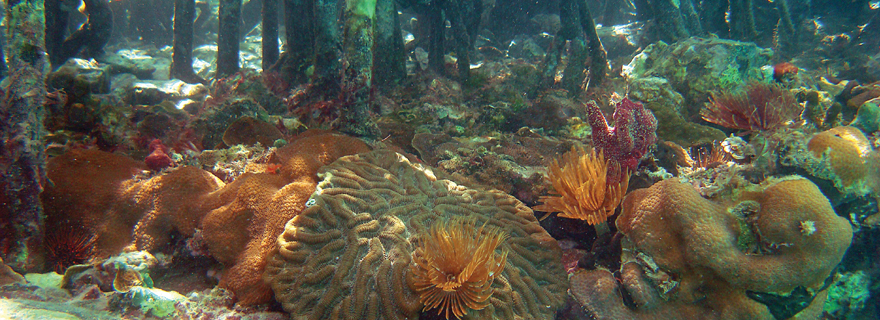

Top Photo by Caroline Rogers, USGS.

Scientists have been detailing the benefits of healthy estuaries for decades – protecting shorelines from erosion and storms, improving water quality, providing vital habitat for economically valuable fish and marine species, and boosting local tourism.

A new study underway in Tampa Bay focuses on yet another benefit: buffering both global and local ecosystems from the effects of increased carbon.

Mangroves, marshes and seagrasses, dubbed “blue carbon” resources, may capture up to 50 times more carbon from the atmosphere than tropical forests, sequestering it in soil where it is less likely to be released. Locally, healthy seagrass beds may create refuges for oysters and other shellfish that are impacted by ocean acidification caused by excess atmospheric carbon.

The Tampa Bay studies expand upon recent research from Puget Sound and the Florida Keys. The Washington study shows that marsh grasses and the sediments they accumulate can capture significant amounts of carbon. In the Keys, corals surrounded by seagrasses may be more protected from ocean acidification than those that live where there is less seagrass.

The study, directed by Restore America’s Estuaries with funding from the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, Tampa Bay Environmental Restoration Fund, Environmental Science Associates and Scotts MiracleGro, will focus on four major questions:

• How much carbon can healthy mangroves, marshes and seagrass capture in Tampa Bay? Globally, sequestration ranges from nearly 140 grams to about 20 grams of carbon per square meter per year, with local results expected to be somewhere in the middle of that 7-fold range.

Are healthy seagrasses minimizing the impact of ocean acidification in Tampa Bay? The effects of acidification are already being seen in coral and shellfish in other areas, but Tampa Bay’s oyster population appears to be healthy and pH in the bay is rising.

• Which uplands should be prioritized for purchase so that important ecosystems can move inland as sea level rises?

• And finally, can wetlands restoration become a viable option for the voluntary carbon market, creating another revenue source for ongoing conservation and restoration initiatives, both in Tampa Bay and around the world?

Multiple benefits to continued habitat restoration

Globally, the emphasis on blue carbon has been on mangroves because they’re larger plants that can sequester significant amounts of carbon in their biomass, capture carbon-laden detritus in their tangled roots and don’t die back in the winter except in extreme cold. In some areas, an acre of mangroves can sequester carbon equal to the annual emissions of 130 automobiles.

In Tampa Bay, where seagrass beds have been the focus of a comprehensive restoration effort for nearly 30 years, scientists will be looking at the potential for storing carbon in underwater grasses as well as creating potential “refuges” for oysters and other shellfish.

“We’re adding about 880 acres of seagrasses per year and as we study carbon sequestration with seagrasses, we’ll need to look at a whole suite of impacts,” said Dave Tomasko, an ESA researcher. “Already, we have twice as many acres of seagrasses as either mangroves or marshes.”

Part of the reason that seagrasses were considered less important than mangroves was the rapid turnover of biomass, which releases the carbon that the plant had captured. As it turns out, that decomposing biomass may react with oxygen and carbonate sediments and “fix” the carbon in a chemical process known as a bicarbonate pathway.

Perhaps even more importantly, that chemical reaction could help reduce ocean acidification. Seawater absorbs about 30% of the excess carbon in the atmosphere, but those higher levels of carbon make seawater more acidic. That acidity, in turn, makes carbonate ions less abundant. Without carbonate ions, calcifying organisms such as oysters, scallops and coral can’t build the structures they need to survive.

Although ocean acidity has increased about 30% on a global scale, acidity levels have been dropping in Tampa Bay since the mid-1980s. Researchers theorize that restoration of seagrass beds may have been an important part of that change.

“Over the past few years we’ve heard about oyster reefs dissolving in the Pacific Northwest, but that doesn’t seem to be happening here,” notes Peter Clark, president of Tampa Bay Watch and current chairman of RAE.

“We’re not sure whether they’re linked or not, but the increase in pH coincided with the seagrass recovery,” adds Ed Sherwood, senior scientist at the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

TBEP, working with the U.S. Geological Survey, hopes to establish a long-term monitoring program to track pH levels in the bay and nearby gulf waters beginning with a small pilot project this year. “There are a number of variables we need to consider,” said Kim Yates, a biogeochemist at USGS in St. Petersburg.

“In the Florida Keys, some coral reefs are surrounded by seagrasses and in the U.S. Virgin Islands reef-building corals are migrating into mangroves,” Yates adds. “Some recent studies indicate that photosynthesis in seagrass beds and mangrove communities buffers ocean acidification enough to create ‘refuges’ for benthic communities, including corals.”

Carbon credits to support ongoing restoration, conservation

An important part of the blue carbon study will be creating a replicable approach for bay managers across the state and nation as part of the voluntary carbon market. Once approved, voluntary blue carbon credits could be used as an additional source of funding for restoration and conservation, said Steve Emmett-Mattox, strategic director of planning for Restore America’s Estuaries.

An important part of the blue carbon study will be creating a replicable approach for bay managers across the state and nation as part of the voluntary carbon market. Once approved, voluntary blue carbon credits could be used as an additional source of funding for restoration and conservation, said Steve Emmett-Mattox, strategic director of planning for Restore America’s Estuaries.

Globally, about $379 million in carbon credits kept about 76 million tons of greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere in 2013, and some suppliers predict the market will triple by 2020. “Since most of the companies involved in the voluntary carbon market say that corporate responsibility is why they are buying credits, offering wetland restoration projects with third-party verification of carbon sequestration would be a significant advantage,” he said.