By James Anthony Schnur

A quick glance at any Florida map reveals the obvious: Pinellas County occupies a peninsula along peninsular Florida. However, a closer examination of the terrain illustrates a fact that few people realize, including residents of Pinellas County’s most populous city: St. Petersburg sits entirely upon a number of islands separated from the rest of the county. The largest island, one comprising most of the city’s ‘mainland,’ has origins as a tract severed from the rest of the mainland a century ago.

In the early 20th century, residents of the central Pinellas peninsula confronted an environmental situation that few would view in negative terms today. Numerous freshwater lakes and marshy areas dotted the landscape. During rainy seasons, an overabundance of water saturated the soils and nourished the aquifer. Residents derived their potable water not from faraway well fields in other counties, but instead from nearby wells and artesian sources. Unfortunately, the same ponds, lakes, and standing water that quenched thirst also complicated farming, discouraged settlement, and sustained clouds of mosquitoes.

During the first decade of the 1900s, two Florida governors shepherded what many viewed as an appropriate course of action during the Progressive Era. Governors William Sherman Jennings (1901-1905) and Napoleon Bonaparte Broward (1905-1909) spent much of their terms of office promoting initiatives to drain the Everglades. At this time, many viewed such a large scale land reclamation project in positive terms. To Jennings, Broward, and others who supported reclamation projects, applying technology to drain the Everglades would allow for the reduction of mosquitoes and other pests while creating new, fertile areas for agriculture.

Although much of the Everglades remained intact, two local initiatives in the 1910s did have the effect of draining substantial portions of central Pinellas as landowners and developers sought to turn ‘useless’ swamplands into rich and fertile fields.

Frank Allston Davis played an important role in the early development of St. Petersburg. In November 1909, Davis and other Pinellas developers that he had known from his days in Philadelphia acquired approximately 10,000 acres of land in central Pinellas, near the railroad line, as part of a partnership known as the Florida Association at Pinellas Park Farms. Before the end of the year, they had sold nearly 1,500 acres and moved forward with plans to build an agricultural colony named Pinellas Park on some of the best ‘muck’ land in the area. They placed advertisements in Pennsylvania newspapers, and attracted buyers who hailed from Altoona, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and other locations.

Summertime rains and poor drainage threatened the potential of the Pinellas Park farming colony. Concerned that saturated soil and marshlands threatened their investment, developers moved forward with plans to establish a drainage district for Pinellas Park. The district incorporated on June 6, 1914. Initial plans called for creating drainage channels that extended Joe’s Creek near Long Bayou. Investors in the Pinellas Park area envisioned a waterway that cut from the Long Bayou area near present-day Seminole and Bay Pines to upper Tampa Bay. Work on the first phase began in 1915.

Dredges and other heavy equipment carved Cross Bayou’s lower area a century ago. In some segments, machines had to remove nearly 18 feet of soil elevated along Cross Bayou, extensions of Joe’s Creek, and other ditches to create what a March 1915 issue of the Pinellas Park Enterprise called the “perfect system of drainage.” The district covered approximately 14,000 acres and some speculators even had dreams of widening the bayou to bring Pinellas Park “close to navigation,” at least for smaller watercraft.

As workers extended the canals into the new town of Pinellas Park during the latter months of 1915, residents of another municipality also discussed water resources and reclamation projects. Incorporated in 1905, Largo quickly grew in stature during its first decade as “Citrus City.” In 1915, nearly 800 approved bonds created a municipally owned water and sewer system. The main source of water came from a well more than 170 feet deep, tapping into the Floridan Aquifer. Homes with one or two faucets could use unlimited water at the rate of one dollar per month, with an extra charge of a quarter per month for homes with baths.

Another notable source of freshwater occupied an area east and southeast of Largo. Once known as “Lake Tolulu,” this 500-acre body of water spanned an area south of Bay Drive, east of Largo Central Park, and west of Starkey Road towards Ulmerton Road. Rechristened Lake Largo in the late 1800s (“largo” means “long” in Spanish), this lake soon gave the community adjacent to it a name. Prior to the 1910s, this long lake served as a source for fish and recreation. As groves and farms expanded, however, the land and nutrient muck under the lake became more valuable than the lake itself.

During the summer and fall of 1915, landowners in the Largo area also began discussing a comprehensive reclamation plan to create a Lake Largo-Cross Bayou Drainage Project. Formally proposed in September 1915 with a budget of $150,000, this project called for the creation of two large canals and over fifty miles of smaller ditches in central Pinellas County between Long Bayou near Bay Pines and Tampa Bay near the present-day site of St. Petersburg-Clearwater International Airport. Once approved, the project would complete the work started by interests in Pinellas Park. Authorities issued bonds in December, and work on this project started in February 1916 and continued into the latter months of 1917.

As the saltwater Cross Bayou canal successfully drained freshwater from the area, the March 29, 1918 issue of the Largo Sentinel newspaper celebrated the transition of the lakebed into “a big plantation”: “While it was a pleasing picture before the drainage work … it is now a much more pleasing picture when one looks out over the hammock lands now in cultivation. … This large tract of reclaimed land shows what drainage is worth to (the acreage east of Largo) which has always been considered practically worthless.”

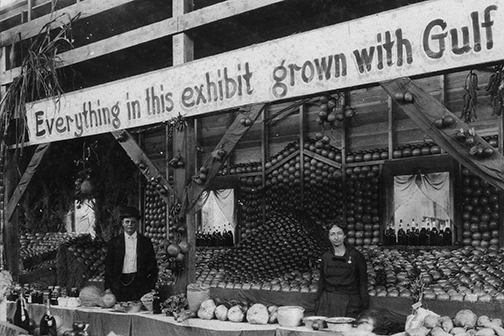

The nutrient-rich mucky soil of the former lakebed brought prosperity to truck farmers in the region. Reclaimed lands needed little if any fertilizer to grow everything from radishes to cabbages, oats to rice, and papaya to pumpkins, not to mention all varieties of citrus.

The draining of Lake Largo and other reclamation projects allowed for the expansion of farms and pasturelands that fed the land boom in St. Petersburg. Tourists in the Sunshine City’s hotels and a growing population of residents on the large ‘island’ of southern Pinellas enjoyed products from the Largo and Pinellas Park areas made possible by land reclamation.

In an ironic twist, after World War II, farmers and grove owners south of the former Lake Largo hoped to create a freshwater lake in a shallow part of Long Bayou. By this time, fears of saltwater intrusion into the aquifer and uncertainty about whether existing freshwater sources could sustain a growing population led to plans to build a dam with a roadway atop it.

In the summer of 1949, workers finished construction of a dam along Long Bayou at the present site of Park Boulevard. Built at a cost of approximately $160,000, this dam allowed water north of Park Boulevard to transform from a shallow saltwater marsh into the freshwater estuary of Lake Seminole. The creation of Lake Seminole was hailed as an important development for farmers and cattle ranchers in the area, such as Jay B. Starkey. Within a decade, homes and trailer parks rapidly replaced the groves and grazing land.

Today, most of the former lakebed of Lake Largo is valued not for the crops yielded, but instead for the buildings and, ironically, swimming pools sitting upon it.

James A. Schnur is the official historian for Pinellas County and a special collections librarian at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg.