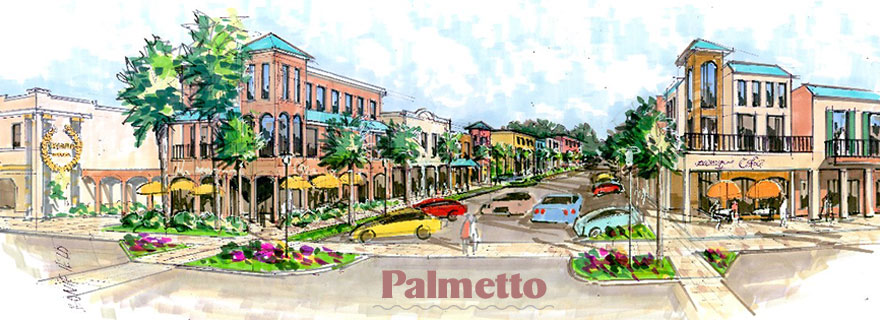

“Palmetto had never done a streetscape before so when we started planning it, we looked at how we could make it aesthetically more pleasing and layer advantages into it so we would have a larger impact,” said Jeff Burton, director of Palmetto’s CRA. “In nearly every conversation, low-impact development – or LID – rose to the top.”

Rather than using standard curb-and-gutter that flows to a treatment pond or facility, LID designs focus on allowing on-site natural features to clean stormwater before it runs off-site. For the city of Palmetto, with a downtown located near the mouth of the Manatee River, it was particularly critical.

“The river has always been the lifeblood of this town,” says Burton. “It was founded in the 1880s as a place where the ship from Tampa would come up the river to pick up produce from farms like the Gamble Mansion.”

[easy-media med=”4500″ size=”300,300″ align=”right”]Stormwater hadn’t been a consideration in previous development — and it showed. “You could stand at any outfall after a rainstorm and see a sheen on the water from the oil on streets and parking lots,” Burton said. “Stormwater flowed straight from the streets to the river.”Designed as a partnership between landscape architect Tom Levin of Ekistics Design Studio and Applied Sciences Consulting, the recently completed retrofit at Fifth Street is both visually appealing and extremely effective at keeping and treating stormwater on-site.

“You can have a pipe in the ground or you can chose an artful, creative way to transmit water,” Levin said. “Rather than sweeping infrastructure dollars under the carpet, you see an outward expression of how it works.”

At the same time, it’s extremely effective at preventing contaminants from flowing into the river, capturing up to six inches of rain and providing 100% treatment on-site. In fact, the Fifth Street design combines all the major components of urban LID to take advantage of specific benefits each offers, according to Elie Araj, ASC president.

Pervious pavement, which works “kind of like Rice Krispies” in soaking up water, is somewhat limited in streetscapes because it doesn’t hold up well to heavy loads or turning movements, but it’s perfect for parking spaces. “You can see water roll off the crown of the driving lane, hit that pervious pavement and sink in almost immediately,” said Derek Doughty, ASC vice president.

[easymedia-gallery med=”4517″ size=”150,150″]While some of the older pervious pavement may not have been as effective over the long term, new technologies have shown to regain 80% of their water-handling capacity after cleaning with a vacuum sweeper, even if they had been totally plugged before, Araj adds.Pavers, both pervious and impervious, were used in the Fifth Street construction, Burton said. They work like the old-fashioned bricks that still line parts of Palmetto’s riverfront neighborhoods – the gaps between pavers are filled with sand that allows water to seep through and into the ground.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]“It definitely helps the private sector when they can purchase a site that’s already in compliance with stormwater regulations,”

— Jeff Burton, director of Palmetto’s CRA.

[/su_pullquote]A series of planters — called green gutters — at street level captures water so that plants can soak up contaminants. “Every plant you see was carefully selected for a reason,” said Jack Merriman, senior environmental scientist with ASC and former environmental scientist for Sarasota County. They’re lined with an oyster shell mulch – another carefully selected alternative because it doesn’t break down or float off and adsorbs contaminants more effectively than other choices.Roof-top stormwater is addressed with a series of waist-high planters built outside a planned development. When the buildings are constructed, pipes will run from the rooftop to the planters where they will store rainwater and allow it to slowly soak into the ground.

While planning and permitting LID construction can be time-consuming, it’s generally less expensive to build and maintain than conventional road construction, said Araj. Instead of using concrete gutters connected to pipes that drain to a stormwater treatment pond, the “pond” is under the road. Land for a pond, particularly in a waterfront urban setting, is both expensive and limits development opportunities, he adds.

Instead of compacting the soil to support a concrete or asphalt road, the road is excavated and the soil underneath it is replaced with fist-size rocks. That leaves a solid foundation for cars and trucks on the road but plenty of room to hold stormwater.

Long-term monitoring is always a consideration, but it may be a challenge with this site. “It’s designed to capture the first six inches of rain – about a 10- to 25-year storm – so we haven’t seen any discharge at all,” Araj said. And while the site has been designed so that any potential overflow moves back through the original drainage system to the river, most of the pollutants are captured in the first inch of rain as it flows across streets and sidewalks so any overflow should be free of contaminants.

[easymedia-gallery med=”4525″ size=”150,150″]Along with successfully treating stormwater, the retrofit is working well in terms of attracting new businesses. The CRA purchased and tore down an ugly old metal building, and the empty site was purchased earlier this year by a businessman who is also renovating the nearby Olympia Theatre as a recording studio.

“It definitely helps the private sector when they can purchase a site that’s already in compliance with stormwater regulations,” Burton said.

With the four-block Fifth Street project complete, Burton and the ASC team are looking at renovating the town’s riverfront marina using technology that both looks great and captures stormwater. Next on the agenda is a six-phase, 17-block retrofit of Main Street, designed to bring businesses back to the town’s central business district.

For Burton, the 48-year-old son of a former mayor of Palmetto, the long-term goal combines financial success for his city with protection for the river he loves. “I grew up on the Manatee River and when I’m done, I hope it’s cleaner than it was when I first got here.”

[su_note note_color=”#4094ad” text_color=”#ffffff”]Learn more:

A presentation by Ekistics and ASC to the Florida Chapter of the American Association of Landscape Architects is online.

[su_button url=”http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.flasla.org/resource/resmgr/2013_speaker_presentations/palmetto_fsa_presentation_re.pdf” target=”blank” style=”flat” background=”#465f7c” radius=”0″ ts_color=”light”]View the Presentation[/su_button][/su_note] [su_divider]